Queue warning systems have been implemented for rural work zones to notify drivers of upcoming stopped traffic. By alerting approaching drivers to slow or stopped traffic in advance, these systems increase driver awareness, help prevent rear-end collisions, and enhance safety in rural corridors where congestion is less expected.

ITS and Rural Communities

2024 Executive Briefing

BRIEFING HIGHLIGHTS

BRIEFING HIGHLIGHTS

- Rural communities face significant safety and mobility challenges such as longer travel distances, limited public transportation options and higher rates of traffic fatalities and injuries.

- ITS applications can help improve safety, mobility, and transportation options in rural communities, by enhancing monitoring, situational awareness and transit operations.

- End-of-Queue warning system deployed in work zones on rural roads in Texas to improve safety serves as a successful case study.

Introduction

Rural communities provide key linkages in America’s transportation system, connecting travelers to economic and recreational opportunities, and distributing freight from distribution centers and core American industries (agriculture, mining, forestry, and manufacturing) to consumer points across the U.S. Rural areas comprise approximately 97% of the U.S. land area and are home to 19% of the population [1] while, 68% percent of America’s road miles are in rural areas (over 6 million miles). Moreover, large volumes of freight either originate in rural areas or are transported through rural areas on the nation’s highways, railways, and inland waterways. Two-thirds of rail freight originates in rural areas, and nearly half of all truck vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) occur on rural roads.

Yet these regions face significant safety and mobility challenges, such as longer travel distances, limited public transportation options, poor transportation infrastructure condition and maintenance, and higher rates of traffic fatalities. For example, when rural roads or bridges are closed, travelers are required to make detours nearly twice as long as those necessitated on urban roads [2]. Also, while 19% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, 43% of all the roadway fatalities occur on rural roads [2]. In fact, the fatality rate in rural areas is 1.87 times higher than in urban areas. This disproportionate rate underscores the critical need for innovative solutions to improve rural transportation safety and efficiency.

The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) has several initiatives and resources to help address the unique challenges of rural roads. These include but are not limited to: Rural Opportunities to Use Transportation for Economic Success (ROUTES), National Center for Rural Road Safety, Rural Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) Toolkit, and ITS4US Deployment Program.

ITS technologies offer an innovative approach to addressing transportation challenges in rural communities. This briefing presents the benefits, costs, and lessons learned associated with ITS deployments in rural context.

Benefits

Safety - Implementation of ITS can lead to significant improvements in rural road safety through real-time monitoring, situational awareness and communication systems that provide timely warnings about hazardous conditions including wildlife crossings, work zone activities and other potential dangers. In line with the Safe Systems approach, ITS can help create a road system that accommodates human mistakes and minimizes crash impacts. Examples of how ITS technologies have been deployed to improve rural road safety are discussed below.

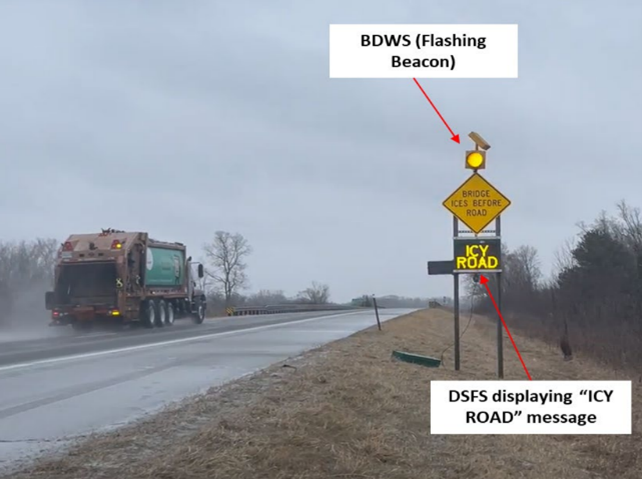

Reducing weather-related crashes: Each year, 24 percent of weather-related vehicle crashes occur under icy, snow and slushy conditions, resulting in over 1,300 fatalities and more than 116,800 injuries [3]. To reduce weather-related vehicle crashes, Michigan implemented an Automated Bridge Warning System designed to mitigate the risks posed by icy bridge conditions. The system activates LEDs on "BRIDGE ICES BEFORE ROAD" signs when conditions exceed certain thresholds, alerting drivers and sending automated messages to the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) and the Delta County Road Commission (DCRC) for timely bridge deck treatment. Since its installation in 2015, the site in Otsego County has experienced a 35 percent reduction in total ice, snow, and slush related crashes. Furthermore, there has been a notable decrease in crash severity, with no fatal or serious crashes occurring since the installation, compared to three such incidents in the years prior (2024-B01854).

Improving work zone safety: Work zones are high-risk areas for crashes due to limited margins for driving error. In 2022, 891 fatalities and 37,701 injuries occurred in work zone crashes, with 38% happening in rural areas. Vehicle strikes caused 45% of worker deaths, while 25% were due to workers driving or riding in vehicles [4]. To mitigate this, Smart Work Zone (SWZ) systems, which include Active Work Zone Awareness Devices (AWADs), connected vehicle technologies and law enforcement vehicles with flashing blue lights, have been implemented to enhance safety and traffic management. AWADs use radar and flashing LED signs to warn drivers of active work zones, displaying messages like "Active Work Zone When Flashing" and "Speeding Fines Doubled". A before-and-after study in Florida found that AWADs alone reduced vehicle speeds by 10%, increased safe driving behavior by 44%, and decreased risky behavior by 43%, particularly under low and moderate traffic conditions. The combination of AWADs and law enforcement was especially effective on rural roads with high-speed limits and significant work zone speed reductions (2023-B01788). On rural roads, the part-width construction method is usually used. This method allows one part to remain open to traffic while the other part remains under construction. This presents safety challenges on driveways and at intersections. Driver Assistance Devices (DADs) can improve traffic operations and safety in work zone by allowing motorists at driveways, particularly on low-volume roads, to join an existing queue of vehicles in the mainline instead of requiring a separate phase at a temporary traffic signal. Safety Impact of DADs were evaluated on four two-lane two-way rural work zones in Ohio. The DADs were found to decrease mainline vehicle speeds by 28% and queue lengths by 32%. A survey conducted with construction personnel revealed that 84.62% of respondents felt the DADs provided improved safety (2023-B01781).

Enhancing Pedestrian Safety: In 2022, about 15% (1,139) of all pedestrian crashes occurred on rural roads, with 77% of all pedestrian fatalities occurring in the dark. Additionally, in rural areas, 63% of pedestrian deaths occurred on roads with speed limits of 55 mph or higher [5]. Low pedestrian visibility and high vehicle speeds are major contributors to these fatalities. One ITS technology that can enhance pedestrian visibility on rural roads is the Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacons (RRFBs). RRFBs are traffic control devices that use flashing yellow lights to alert drivers that pedestrians are crossing the road at marked crosswalks or uncontrolled intersections. The effectiveness of RRFBs was evaluated at six locations on rural roads using video data collected under different traffic conditions. A before-and-after analysis showed that RRFBs resulted in an improvement in driver yield rates of 12 to 43 percent, and drivers were 2.59 times more likely to yield to pedestrians (2023-B01776).

Improved Intersection Safety: Intersections are inherently risky due to the conflict points where vehicle paths intersect, contributing to approximately one-quarter of all traffic fatalities and about half of all traffic injuries in the United States. In 2021, there were 11,799 fatalities in intersection crashes, with 25% occurring in rural areas [6]. ITS technologies such as the Integrated Intelligent Intersection Control System (III-CS) have been used to improve the safety of intersections. The III-CS is designed to minimize the likelihood of rear-end collisions, reduce overall traffic delays, and detect red-light running vehicles using a green time termination and all-red extension algorithm. The III-CS was deployed at an intersection on Maryland State Route 4 in Prince George’s County. A before and after deployment evaluation showed that the average hourly number of vehicles in the dilemma zone—a critical factor for collision risk—decreased by approximately 18%, from 48.3 vehicles per hour (vph) before deployment to 39.7 and 39.4 vph after deployment. Additionally, driver behavior became less aggressive over time. The rate of red-light-running vehicles also decreased, from 0.119 per cycle before deployment to 0.063 and 0.116 per cycle after deployment (2022-B01657).

Enhanced Animal Detection: Vehicle crashes involving animals are a significant safety concern in the United States, especially in rural areas (21.0 percent of all crashes on two-lane rural roads, but only 1.4 percent of crashes on urban roads [7]). Each year, these types of crashes lead to numerous injuries, fatalities, and substantial economic losses. According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), in 2022 motor vehicle crashes involving animals resulted in 184 deaths [8]. To reduce animal-vehicle collisions, a radar-based animal detection system was deployed on U.S. Highway 95 in Bonners Ferry, Idaho. This system uses Doppler radar to detect large mammals, such as deer and elk, as they approach the highway. Once an animal is detected, warning signs are activated to alert drivers, allowing them to respond accordingly. Evaluation of the system showed that up to 85% of deer were detected in time for drivers to react accordingly. The system was also found to be effective in reducing vehicle speeds by up to 4.43 mph, even under challenging weather conditions (2021-B01581).

Mobility – Mobility challenges in rural communities in the United States are significant and multifaceted, requiring people to make longer trips, negatively impacting residents' ability to reach essential services, economic opportunities, and overall quality of life. Several ITS technologies have been deployed to improve mobility in rural communities, example of which are discussed below.

Improving Transit Operations: While transit is sometimes perceived as a solution available only for urban areas, there is demand and capacity for it in rural areas. More than 1 million households in predominantly rural counties do not own a personal vehicle [9]. Rural residents without cars face unique barriers as alternate options are not always available and affordable. For example, older adults who no longer drive make 15% fewer trips to the doctor, 59% fewer trips for shopping or dining out, and 65% fewer trips to visit friends and family compared to their driving peers [10]. Residents of rural communities are also faced with the added challenge of planning their trips. The Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans) developed a trip planner named Go! Vermont, that provides the public (especially rural residents) with a mobile application to facilitate transit trip planning. The application uses General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS)-Flex data to provide flexible transit options such as route deviation and dial-a-ride. Evaluation of the application usage data over a one-year period showed a 16 percent increase in the average number of daily website visitors and a survey of transit operator surveys revealed that 46 percent of the respondents reported that Go! Vermont was better for trip planning than other public navigation tools (2023-B01792).

Improving First Mile/Last Mile Transportation: First mile/last mile (FMLM) services, which refer to the initial and final legs of a journey connecting travelers from their starting points to public transportation hubs and from those hubs to their final destinations, face unique challenges in rural areas. Due to the low population density in rural areas public transportation options like shuttles may not be economically viable because of the limited number of potential riders. Also limited infrastructure such as absence of sidewalks or bike lanes also limits non-motorized transportation options, making it harder for residents to safely reach transportation hubs. Bridging the first and last mile transit connectivity gap in rural areas has become imperative to improve mobility. Emerging ITS technologies, such as autonomous shuttles can offer solutions to first mile/last mile (FMLM) challenges. The North Carolina DOT conducted a pilot of an electric automated shuttle, called the “Connected Autonomous Shuttle Supporting Innovation” (CASSI). The shuttle was equipped with various sensors (e.g., lidar, radar, and camera units) and an automated driving system (ADS) capable of operating at Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) automation Level 4 (High Driving Automation). The shuttle operated for 64 days and served 3,380 riders with a total of 809 trips. Assessment of the performance of the shuttle showed that Nearly 90 percent of shuttle riders felt that the shuttle arrived at their stop within a reasonable amount of time (2022-B01700).

Costs

Implementing ITS technology in rural communities involves evaluating several cost factors, such as the scale of infrastructure and the specific technologies required. Costs are also influenced by the complexity of the system, the extent of coverage, and the need for ongoing maintenance and support. Table one summarizes examples of ITS solutions to improve safety and their associated cost.

Table 1: ITS Solutions and Associated Cost

| ITS Solution | Description | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Driver Assistance Devices (DADs) | DADs enable motorists at driveways, particularly on intersecting roads with low traffic volumes, to merge into an existing queue of vehicles on the main roadway in the same direction of travel, rather than calling an additional phase at the temporary traffic signal specifically for driveway movements. | Ohio DOT estimates indicate that the capital cost for DADs in one-lane, two-way work zones is $16,200 (at $1,800 per month, for nine months). Similarly, the maintenance cost for DADs was estimated as $4,500 (accruing at $750 per six weeks). In total, the capital plus maintenance costs for DADs over the nine-month construction period was estimated to be $20,700 (2023-SC00538). |

| Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacon (RRFB) | An RRFB is a traffic control device designed to improve the visibility of marked crosswalks, particularly those at uncontrolled locations, such as mid-block crossings. RRFBs consist of pushbutton-activated flashing beacons that enhance standard crosswalk signage. | Estimates from the VTrans show that the typical cost per crosswalk (including materials, equipment, and labor) is $10,000 (2024- SC00554). |

| Doppler Radar-Based Animal Detection System | The system utilizes doppler radar to detect large mammals, such as deer and elk, as they approach the highway. Detection is based on several parameters including the size of the object, its speed, and the direction of movement. | Based on Idaho’s DOT estimates, a doppler radar-based animal detection system with continuous coverage would cost about $60,000 per 820 feet and would require replacement every 10 years. Maintenance and calibration cost an additional $3,000 per 820 feet annually (2021-SC00486). |

| Fully Automated Shuttle | Fully automated shuttles, provide an innovative solution for short-distance travel in both urban and rural settings. They are characterized by their compact size and designed to operate on set routes at low speeds. | Researchers estimated the vehicle cost of a fully automated shuttle with a capacity of 12 to 15 passengers to range from $225,000 to $250,000, with annual operation costs ranging from $15,000 to $100,000 (2024-SC00553). |

Best Practices

ITS applications that support rural communities are numerous, but certain best practices are applicable across most scenarios. Below are lessons learned, and best practices related to some of the ITS technologies discussed above. These insights from past projects help refine and enhance best practices for future initiatives.

- Radar-based Animal Detection Systems

- When developing radar-based animal detection systems, consider extending the duration that warning signs remain activated after the last detection. Alternatively, adjust the radar configuration to detect large mammals earlier and reduce the gaps between consecutive detections of animals approaching the highway. Researchers recommend using LED signs that are only activated when a large mammal is detected (2021-L01041).

- Signs should be placed at the beginning and end of the detection zone, marked as "START DETECTION ZONE" and "END DETECTION ZONE." It is recommended to position the first warning sign at least 477-566 feet before the start of the detection zone. Additional warning signs should be placed at intervals throughout the detection zone, continuing until the end of the zone (2021-L01041).

- Automated Shuttles

- Specify the automated shuttle operation guidance that operators should follow to ensure consistent operations. Training should include detailed guidance to address potential safety conflicts, ensuring uniform procedures among all shuttle operators (2022-L01164).

- Provide clear signage at vehicle stops and be prepared to address any participant confusion caused by unexpected vehicle behaviors. Ensure that signage includes detailed information about service frequency, routes, and rules to prevent confusion (2022-L01164).

Success Story

In rural areas, drivers typically do not expect traffic queues, especially at night, which can lead to crashes. To address this issue on a predominantly rural section of Interstate 35 (I-35), the Texas DOT developed and deployed an innovative End-of-Queue warning system (2020-B01510). This system was designed to mitigate crashes caused by frequent temporary nighttime lane closures, which often led to traffic queues upstream of the merging taper. The queues raised several concerns:

- The rural nature of the corridor made nighttime traffic queues particularly unexpected for drivers.

- The varying locations and frequency of lane closures each night prevented drivers from anticipating queues.

- Construction activities utilized all available right-of-way, making it difficult to keep queue warning equipment in place.

- The corridor is heavily trafficked by large trucks, increasing the risk and severity of end-of-queue crashes.

The end-of-queue warning system consists of two main components:

- Portable Work Zone Queue Detection and Warning System: A highly portable work zone ITS is deployed upstream of the merging taper each night when queues are expected. It is removed the next morning along with the merging taper.

- Portable Rumble Strips: These are deployed in the travel lanes upstream of the merging taper to provide drivers with tactile, audible, and visual alerts as they approach a lane closure.

The system's initial setup included four portable speed sensors deployed from the merging taper up to 2.5 miles upstream, a portable changeable message sign (PCMS) positioned 3.5 miles from the taper, and portable rumble strips beginning at 3.75 miles from the taper. A second deployment plan extended the warning range to 7.5 miles, using eight sensors, two PCMS units, and two sets of rumble strips. A pre-designed PCMS message warns drivers of stopped or slowed traffic ahead, with the message selected based on the speed detected by each sensor. Project personnel input planned lane closures into a database that tracks all pending closures. An input-output analysis of expected traffic volumes versus work zone capacity is automatically performed for each planned lane closure. If queues are projected for the following evening, a deployment plan covering the maximum expected queue length is implemented as part of the temporary traffic control setup. The system was deployed during over 200 nighttime lane closures, resulting in the following outcomes:

- Crash reductions of 18% to 45%, compared to estimated crash rates without the system.

- A decrease in rear-end collisions and severe crashes (injury or fatal) at lane closures where the system was used, compared to similar closures without the system.

- Societal cost savings between $1.4 million and $1.8 million, with ongoing savings of $6,600 to $10,000 per night of deployment.

References

- United States Census Bureau, “What is Rural America?”, Aug. 09, 2017. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2017/08/rural-america.html#:~:text=Urban%20areas%20make%20up%20only,Census%20Bureau%20%2D%20O pens%20as%20PDF. (accessed Aug. 2024).

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Rural Transportation Statistics”, Aug. 16, 2022. https://www.bts.gov/rural (accessed Aug. 2024)

- Federal Highway Administration, “Snow and Ice”, Feb 1, 2023. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/weather/weather_events/snow_ice.htm#:~:text=Each%20year%2C%202 4%20percent%20of,slushy%20or%20icy%20pavement%20annually. (accessed Aug. 2024).

- National Workzone Safety, “Worker Fatalities and Injuries at Road Construction Sites”, https://workzonesafety.org/work-zone-data/worker-fatalities-and-injuries-at-road-construction-sites/ (accessed Aug. 2024)

- IIHS, “Fatality Facts 2022 - Pedestrians”, June 2024. https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/pedestrians (accessed Aug. 2024)

- National Highway Traffic Administration, “Rural/Urban Comparison of Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities”, May 2024. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/813488.pdf (accessed Aug. 2024)

- IIHS, “Fatality Facts 2022 - Collisions with fixed objects and animals”, June 2024. https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/collisions-with-fixed-objects-and-animals (accessed Aug. 2024)

- Federal Highway Administration, “Investigation of Crashes with Animals”, March 1995. https://highways.dot.gov/research/publications/safety/hsis/FHWA-RD-94-156 (accessed 2024)

- Transportation for America, “More than one million households without a car in rural America need better transit”, May 15, 2020. https://t4america.org/2020/05/15/more-than-one-million-households-without-a-car-in-rural-america-need-better-transit/ (accessed Aug. 2024)

- McGraw Hill Global Institute, “Aging and Urbanization Principles for Creating Sustainable, Growth-Oriented and Age-Friendly Cities”, January 2016. https://globalcoalitiononaging.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/AgingUrbanization_115.pdf (accessed Aug. 2024)